|

|

|

|

INTRODUCTION

The turtle that appeared on the window of an empty shop in Pier Street Altona (a legendary teller of stories) takes up again the story of the birth of Turtle Video.

Why Altona as a spot

for a Community Access Video Centre

and who recommended it? |

“As I said before”, began the turtle, “these are intriguing questions – and not easy to answer.

What recommendations were behind Canberra’s Film and Television Board decision to include Altona in the video access project? Why did the federal Department of Urban and Regional Development (DURD) recommend Altona to the Film and TV Board and underwrite the cost?

Ask 100 people who knew Altona at the time” said the turtle. “You would probably come no closer to the answers.

I’ve thought about it a lot” the turtle continued, frowning. “When you come to look for possible reasons for the choice of Altona, they would have to include:

• the social make-up of Altona – particularly its migrant population;

• the place of Altona on the frontier of Melbourne’s western expansion;

• the large petrochemical industry based there;

• finally, administrative convenience.

Here is where we had reached in Part One of our story” said the turtle.

“1974 seemed a promising year for community video.

The federal government’s Film and TV Board (FTVB) set up 10 Community Access Video Centres (CAVCs) around mainland Australia.

It meant something else as well…

It locked-in a one-size-fits-all model for financing community access video.

It locked-out any possibility of federal money being available for alternative community video projects in the near future.

It locked-out the ability to tailor resources (people and equipment) to the make-up of particular community settings,

It missed out on the opportunity of providing colour video. Colour test transmissions would soon begin on broadcast television but portable colour video recorders were unavailable. However, Western Communications demonstrated only a year or so down the track that a hybrid Super 8/video cassette system was possible.

The trouble was Canberra was in a hurry.

There was a view abroad in the national capital that they might not have much time.

The Labour government, with its emphasis on ‘It’s Time’ for social change might not be elected for second term.

So, the community access video centres were rushed into existence.”

The Turtle paused, again frowning.

“You see”, it said, “we turtles are determined creatures.

We are unembarrassed about moving slowly.”

Then – almost as an aside – “You could learn from us.

In a more laidback time the FTVB and DURD might have explored

more thoroughly, ways of supporting community-based videomaking.

In 1973, they didn’t.

But that’s a story for another day.”

|

‘THE TWO WESTS’

‘Whatever happened to Green Valley’ was a co-operative film project – made in Sydney in 1973.

It was a milestone in the history of community based film/videomaking in Australia.

It was made as a response to the battering the western-Sydney suburb was taking in the city’s mass media.

The film’s director cites as typical, views put to him by a Sydney transport worker; views gained from the Sydney media.

• Green Valley – it’s Dodge City isn’t it? (because of all the debt dodgers there)

• Green Valley residents belong to the criminal class; if not all of them then most.

• It would be unwise to eat or drink there – there might be something in the water!

A similar view was abroad about Melbourne’s western region.

In a Melbourne newspaper supplement several years later, John Timlin wrote

As ‘The Age’ recently reported the west (of Melbourne)

has less of everything except

heavy pollution, noxious industries and social problems.

In the media and in the eyes of most of Sydney and Melbourne

the western regions of Australia’s two largest cities

were mostly unappreciated, unloved and unlovely.

This was not the only view of the two western regions

but it prevailed among outsiders and it was strong.

What, if anything, to do about it? |

The Labour Party had come to power in Canberra in 1972.

Rare for a national government it brought with it a major policy platform directed to the future of Australia’s big cities.

DURD was Canberra’s instrument to give a leg-up to regions suffering from long-standing neglect. DURD developed the view that by linking ‘the two wests’ in the public mind its plans for improving the quality of life there would be more readily accepted than if it concentrated on western Sydney or Melbourne.*

DURD hoped that community access video could contribute to their plans.

Independently of ‘the two wests’ strategy there was reason for DURD to involve itself in Melbourne’s west.”

“Remember, I mentioned earlier” said the turtle “that Melbourne’s population was growing fast. Thousands of houses were being built to accommodate the growth. Most were in the south and east: far fewer in the west.

Town planners, social planners, engineers, city councils, debated this ‘lop-sided’ pattern of growth. Should it be accepted as inevitable; a ‘force of nature’?

There was a plan for Melbourne to develop in a corridor along the rail line into Gippsland. It would mean Melbourne’s Central Business District would be down one end, no longer the heart of the metropolis. The character of future Melbourne was at stake. The alternative was to promote development to the city’s west.

AGAINST; “You won’t succeed”, was the response. “In the public’s mind the west is all heavy transport, heavy industry and, beyond that, boring plains. You can’t get people to live there. You’d be fighting a hundred years of history.”

FOR; “Well, we’ll just have to clean things up. Clean up the image. Clean up the reality behind it. Clean up the waterways. Turn near-city land that lies idle or underused into prime real estate!”

DURD saw itself in the pro-west camp.

It would be part of the ‘clean-up’

renovating old infrastructure, encouraging new. |

Supporters of the ‘develop the west’ cause were unlikely to locate scarce community video resources to Melbourne’s Outer East.

They influenced the decision to locate centres at Footscray and Altona.”

FOOTSCRAY

“I want to say”, said the turtle as it continued its story, “when DURD spoke of ‘the deprived west’, it was saying that much of the physical infrastructure had been allowed to deteriorate, needed to be upgraded and added to.

It was not saying the area lacked valuable citizenry.

Following his quote (above) on the image of Footscray held by many outside its boundaries John Timlin wrote:

“For 30 years, on and off, I lived in Footscray … No other town has

given me a greater sense of cohesion and community.”

In an adjoining article, Peter Wilmott wrote:

“Speak ill of Footscray to residents of 20 years or more

and you’re liable to cop a punch in the face.”

Here Peter Wilmott draws attention to two different views of Footscray (and the rest of the inner west).

To outsiders it is exhaust smoke, meatworks and poverty.

To insiders it is a valued place to which they are fiercely loyal.

The inner west was an area

where a strong sense of local community could still be found. |

So Footscray was not all doom and gloom!

It was a natural location for a community access video centre.

• It was the heart of the region.

• Most locals travelled around on public transport via the three railway stations and the suburb’s unique trams. They knew their suburb well.

• The ‘Western Oval’ was the home ground of the region’s Australian Football team – the ‘Bulldogs’.

• The Footscray mall was among the first of its kind in post-war Australia.

• Local trade unions had a history of commitment to both workplace and community well-being.

The place chosen by DURD to house a community access video centre in Footscray was the Trade Union Health Centre.

This was the same location for community video access proposed a year earlier by the ‘Video Exchange’. People in the union movement and people in the coalition of inner-suburban residents associations were strong supporters of bringing community video access to Footscray.”

ALTONA

“So .... if you had decided to set up a CAVC in Footscray and wanted to add a second one in Melbourne’s west to implement the ‘two wests’ policy ....

why choose Altona?

It was an interesting choice.

It was by no means an obvious one.

In 1977 FTVB video project office Bill Childs wrote that he had often been asked ‘What research or advice was relied on to decide

the location of individual centres?’

The answer, he wrote, was – ‘None.’

We can say what was not a reason.

It was not to build on local experience with video or film. This had been behind the setting up of the Green Valley centre in Sydney’s west. It was behind the decision to locate community access video in the building in Carlton occupied by the national office of the Australian Union of Students. The Union had sponsored a pioneering community video project by the group ‘Bush Video’.

No such history lay behind the selection of Altona as a site for community video.

What was behind DURD’s decision?

Was it the physical and social character of the area?

Was it the make up of its community? |

1. THE SOCIAL MAKE UP OF ALTONA

DURD had a profile of the characteristics of communities that warranted its support. It is outline in a 1975 report on the video centres.

‘The Australian government has been quite explicit in its concern that many Australian communities, particularly in industrial towns and the newer working class suburbs

(a) are markedly lacking in community spirit and organized effort at community self-help.

(b) Are served by poor or inadequate community facilities.

(c) Are characterized by high rates of vandalism, delinquency, suicide, mental ill health, broken families and

(d) other such signs of disassociation of the motives of community members.’

Did Altona fit this profile?

If you had lived in Altona in the early 1970’s would you have recognised this as a description of your suburb?

Broadmeadows in the northern west was well known through the media as a social hot-spot But Altona? To the locals it was working class. But ‘problem city’ – no way! Motorists knew it as the night time fairyland of lights south of the highway as they drive to or from Geelong. Most outsiders knew little of it and not a few would have struggled to find it on a map.

It had been an independent municipality for nearly 20 years with growing infrastructure of which locals were proud. It was not that Melbourne knew about it and turned its back on Altona. It was rather that it had not yet been discovered. ‘The Esplanade’ where houses today can sell for a million dollars was still a local secret.”

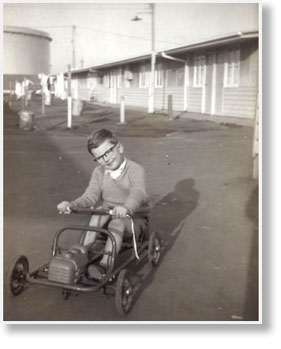

“A part of the Altona population has not been mentioned so far.”

Said the turtle.

“Altona was home to many families who had come to Australia

as migrants and refugees. The first wave came from Britain followed

later by new settlers from continental Europe.

Their first days in the area were as residents of local migrant hostels.

Many of the men found work in the construction and operation of

Altona’s petrochemical industry.

The newcomers were there to stay – and pleased to be.” |

“There are many stories of these new settlers.

An ex-Yorkshire miner was happy to have swapped a lifetime down the mines for a regular job in a pharmaceutical factory: a bit of white powder on your work clothes was infinitely better than coal dust in your lungs.

A refugee from Soviet occupation of the old homeland thrived in the freedom offered by the new one.

Many became permanent locals. They started buying their own homes.

In the port of Williamstown there were older houses occupied by tenants.

In Altona nearly everyone was buying their own house. In time, they would be

home-owners. You could even come across a reverse sense of superiority over Williamstown.

The migrant communities were a reason, in some minds, for locating a community access video centre in Altona.

For the children of migrants and refugees it could

• celebrate values of the cultural life that their family had brought;

• see it as part of a wider multi-cultural Australia into which they had settled.

The new settlers’ commitment to the future

was a positive reason for bringing community video to Altona.

It was not disadvantage and dysfunction that lay behind the decision,

but Altona’s strengths – to underpin Melbourne’s spread west. |

2. ON THE FRONTIER OF MELBOURNE’S WESTWARD EXPANSION

Altona was at the western fringe of metropolitan Melbourne. Beyond its newest houses stretched plains – all the way to western Victoria’s sheep country.

Melbourne had spread rapidly in preceding years to the east and south. There were signs that Melbourne was beginning to sprawl westwards. Not many were aware of them. Perhaps DURD could see signs.

Rather than working class suburbs being the last to get things,

let them for once, be among the first.

Establish a community communications infrastructure in the early

days of a suburb’s settlement to help build a sense of community

and be a means of community self-help. |

This would have been a good reason to locate an experimental CAVC in Altona”,

said the turtle. ”It was a view common among community workers but I don’t know if it was ever put on paper.”

3. THE PETROCHEMICAL INDUSTRY

“Altona was the centre of a large petrochemical complex. The industry provided jobs that locals valued. The complex also emitted a smell to which some locals objected. Most accepted it as a minor nuisance you put up with as a price for readily available work. Some objected. But was the smell a sign that all might not be well?

Might the petrochemical complex be a threat to the well-being of locals?

Might it become a threat?

The influence of the Canadian ‘Challenge for Change’ program was at work here. This film and video project of the Canadian National Film Board was seen as an activist model for Australia by people interested in community.

They saw it as a ‘how-to’ example for taking up the fight against threats to communal well-being. It would make possible two-way communications between company and community.

A CAVC would be a communications resource locals could use to monitor and publicise the effects of the industry on natural and human environments. Such a role for an Altona CAVC was mentioned to Turtle People – at the time of the centre’s establishment.”

CONCLUSION

“My story for you”, said the turtle, “has been an oral history, a gathering of recollections. There are references to printed sources. But at the heart, the story is based on what some of the people of Melbourne’s west remember.

These were people who knew of or were part of the two CAVCs at Altona and Footscray:

Active local residents

Community development workers

Trade Unionists

Local councillors

DURD and Western Region Council for Social Development staff.

It draws on - what they knew, what they talked about, what they didn’t know.

In 1977 FTVB video project officer Bill Childs wrote:

DURD of course, in its high pressure fashion, had a series of logical reasons for choosing the locations nominated.

Phrases like “section 96”, “Area Improvement Programme boundaries”, “tied grants”, “future commitments”, etc. etc., were used to steamroller the Board into accepting DURD’s conditions.

“ At this point, the turtle had a determined look on its face.

“Child’s comments reflected the frustrations of interdepartmental relations in Canberra”, the turtle continued. “It doesn’t mean substantial reasons didn’t exist.

They did.

Reasons for setting up the Altona Community Access Video Centre

were formed in Melbourne’s west – and

they were not arbitrary. |

They include:

A commitment to Melbourne’s part of a ‘Two Wests’ policy to upgrade the region’s infrastructure. This included neglected existing infrastructure and – in the case of the CAVCs – setting up new infrastructure.

The Altona migrant community was a resource to build on. It was one of a number of the area’s recognized strengths. Altona could be an example of community development as Melbourne spread westwards.

The Altona petrochemical complex was a large-scale energy installation. If protective systems failed or were not followed properly what would be the impact on the Altona environment? A community watchdog would be a valuable resource. A CAVC might become part of a watching brief.

There may have been other reasons I have been unable to recover”, said the turtle. “There may be memories out there I have not drawn on. To get any further will take a major study. Until then, if your memory is different to mine, let me know. If you know people whose stories could be added to this one, let me know.”

“If I may”, the turtle said with a rare shy look on its face,

“I will conclude with a couple of observations of my own.

As I said at the start of this story, community access video centres were born in the time of changing communal life. It was also a time of optimism. It was a time when experiments were made and there was money to support them. Neither the optimism nor the finance was long lasting.

But a start was made towards what today is known as ‘social media’. Alongside public transport and public housing

a modern

democratic society needs public communications infrastructure.

COMMUNITY ACCESS VIDEO – A FORETASTE OF

‘THE SOCIAL MEDIA REVOLUTION’?” |

|

|